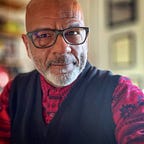

Bert Williams — Harlem and Broadway’s Renowned ‘Nobody’ and Everyman

W.C. Fields called him “the funniest man I ever saw, and the saddest man I ever knew.” The funny and sad man in question was African American actor Bert Williams, one of the preeminent vaudeville stars of his time, who died on March 4, 1922.

From Williams & Walker to the Ziegfeld Follies

From the 1890s, Bert Williams and his partner George Walker triumphed on showbiz stages from San Francisco to New York. Although African American, they were forced to capitulate to the stereotypical minstrel devices of wearing blackface, yet transcended their theatrical masks with effusive talent.

In Dahomey was their groundbreaking hit. Produced by Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon, the show opened at the New York Theatre on February 18, 1903, and became the first all-black musical on an indoor Broadway stage. Others had been booked on theater rooftops, a once-common performance venue that, sadly, theaters rarely anymore use. The show’s success soon carried the entire cast to London’s Shaftesbury Theatre, and to a command performance for the Prince of Wales at Buckingham Palace.

In Dahomey’s London run occasioned the Williams & Walker company to visit to Edinburgh, Scotland, where Master Masons of the Waverly Lodge № 597 initiated, passed and raised nine members of the African-American theater troop into its fraternity.

While in Europe, Williams was also said to have studied pantomime with Pietro, a foremost practitioner of the art at the time. Williams’s mastery of mime technique transformed his face into an expressive tour de force. He perfected the stage persona of a hapless, doleful soul “whose persistent ill-luck somehow endeared us to our hearts,” Jessie Fauset observed in The Crisis. The archetype, which prefigured Charlie Chaplin’s immortal Little Tramp, secured Williams’s fame and fortune.

Show business aside, Williams was no stranger to civic matters. In fact, around 1909, he co-founded the Equity Congress, a self-subsidized Harlem civic organization that championed Black city and state legislative representation, the securing of Black police officers and firemen, and the establishment of a Black New York State military regiment. The last materialized in the form of the 15th Regiment (369th Infantry), best known as the legendary Harlem Hell Fighters.

On June 20, 1910, Bert Williams embarked on the most notable leg of a solo career. (The William and Walker partnership had recently dissolved, and the latter died in 1911.) Williams joined Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies of 1910, in which comedian Fanny Brice also made her debut. For Williams, recently promoted as “the greatest and most original comedian in the world,” it marked the highest benchmark of a black actor enjoying equal stage billing with white colleagues. Williams also signed an exclusive recording contract with Columbia around this time.

Two funerals

Despite critical success, Bert Williams took leave of the Follies for artistic differences. In August 1918, the Crisis reported that Williams “has left that company, alleging that while his name was carried to help the show, his parts have not been commensurate with his ability or reputation.”

And despite his reputation, Williams still faced racial barriers typified in an often related encounter at a bar in the elegant Hotel Astor. When the white bartender told Williams a drink would cost him $50, the black actor accepted the condition without demur. He withdrew a roll of $100-bills from his pocket and ordered drinks around the room for everybody.

“Nobody,” Williams’ signature song from 1905, conveyed much of the artist’s doleful aperçus, and sold upwards of 100,000 copies into the 1930s.

Williams literally worked himself to death after the Follies. In 1922, he collapsed while performing in a farce called Under the Bamboo Tree in Detroit, then returned home to New York. He died at home at 2309 Seventh Avenue in Harlem on March 4.

Reports of Williams’ death generated two separate funeral services. Some 5,000 people reportedly filled Harlem’s St. Phillip’s Episcopal Church uptown on West 134th Street. Right afterward, some 2,000 people overflowed the 1,200-seat Grand Lodge room of the Masonic Temple at 71 West 23rd Street.

The latter funeral constituted the first instance of a white masonic lodge in New York State — St. Cecile Lodge No. 568 — holding services in honor of an African American. The lamb skin that the Waverley Lodge 597 had presented Williams in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1904, was placed along with some symbolic sprigs of acacia in his coffin.

In paying tribute, many mourners inevitably pointed up that Williams & Walker had opened the doors for Broadway’s latest sensation, Shuffle Along. The orchestra of the all-black revue opened and closed the service with Handel’s Largo and Chopin’s Funeral March. Bert Williams was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.